So, I’m not entirely sure how it happened, but somewhere online I stumbled across the gold nugget that is Kuzhali Manickavel’s blog. I suspect it is through the Café Irreal website where she is published, or perhaps through the network of hyperlinked blogrolls that exists across WordPress and Blogspot, but it no longer matters, because I suspect there has been an inner Kuzhali in me all along, just waiting to be discovered.

So, I’m not entirely sure how it happened, but somewhere online I stumbled across the gold nugget that is Kuzhali Manickavel’s blog. I suspect it is through the Café Irreal website where she is published, or perhaps through the network of hyperlinked blogrolls that exists across WordPress and Blogspot, but it no longer matters, because I suspect there has been an inner Kuzhali in me all along, just waiting to be discovered.

Kuzhali is what is known as an emerging writer; she hasn’t written a full-length novel or book yet. But she has flash fiction and short fiction published across the Internet and the wonderful Blaft Publications found her and published most of those stories as a collection, Insects are Just Like You and Me Except Some of Them Have Wings. Blaft also tweeted twice about my Charu Nivedita review, so I am gratefully (and shamelessly) plugging another worthy book of theirs.

I have long maintained that writing humour is one of the hardest genres to write, satire even more so. I have also secretly harboured a dream of writing the modern Indian version of A Modest Proposal. Well, I was SO wrong; clearly, Kuzhali should be the one to write it. Not only has she got the incision skills of a surgeon with her words, she has that sense of tragicomedy, a certain je ne sais quoi that makes satire tick.

IaJLYaMESoTHW (egads, what an acronym for a book title) has 35 stories, some very short, some just short enough and some that are long enough to really dwell on. Not all of them have insects in them, but most do. But the voice that shines through, both in tone, form and content is highly original and imaginative. Kuzhali has definite skill with simile and metaphor, all delivered with stinging effect (haha). There were several moments where I felt Bruno Schulz-like undertones to the writing, in a less dense, more grounded way, like these:

Mrs. Krishnan is wearing a blue sari today. She looks like she has draped the sea over her shoulder and I tell her so. A black handbag hangs from her arm like a dead crow but I decide not to tell her that.

(Mrs. Krishnan)

and

Kalai spent the rest of her afternoon listening to her hands. The heat was making them swell up; she could hear millions of dead seeds and dried tubers jostling against her bones and skin. She feel asleep in her chair and dreamed her hands were huge balloons. They carried her over ships filled with sailors who whistled at her and said hey girliegirlie. She tried to whistle back but ended up spitting at them. The sailors started spitting back at her and Kalai wished she had winked at them instead.

(Monsoon Girls)

Other times, the writing is just sheer amusement:

After breakfast, I start writing my Letter of Explanation to T.S. Eliot. I have already written one to Philip Larkin and I have made a paper tree for Samuel Beckett because I feel he would appreciate the tree more than the explanation. I have also written a note on the power of positive thinking for Sylvia Plath. I pull out a piece of yellow paper and a black fountain pen.

Dear Mr. Eliot,

I am writing to tell you that I am going to fail my paper on 20th century literature because I plan on answering all questions concerning The Waste Land in a made-up language that will only consist of the letters y and p. I want you to know that it’s not you, it’s me. I’m sure you were a nice man, even though you worked in a bank. If I had known you, I promise I would have loved you.

(Jam That Bread of Life)

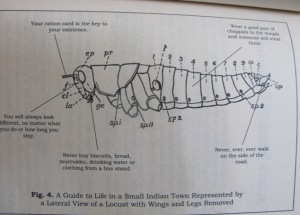

and there’s also some amusing diagrams of dismembered/mutant insects depicting… life situations, for lack of a better term.

The result is a 21st century mutant child of Jane Austen and Evelyn Waugh, both of whom wrote witty, deeply funny and highly relevant dark comedies of manners. And yet, the targets of Kuzhali’s stories are not complex social structures but our human-insect selves, the curiously complex, stratified self. The characters possess strangeness on multiple levels and are wholly unpredictable. Their love is trying and tiring, family is oblivious or carelessly cruel, and the characters share strange affinities with the insect world.

Every morning Velu brought her something different — a large black spider, a broken rainbow beetle, a butterfly with a torn wing. Velu would palce them on her table like flowers and tell her how he was bitten by a scorpion when he was a boy, how his uncle had died of a snakebite. Alarmel would fold each insect into a piece of paper and write things like:

For now the way is very clear for measuring the atmosphere

Shells and ships travel in clips and crash against our fingertips.The bottle was now a clogged and crumbly mess of bodies, some of which had completely turned to dust. Alarmel bought a sheet of white foolscap paper and copied down everything she had written so far in her notebook.Instead of listing the phrases, she let them run into each other like an unending train of words. When she was finished, she read it back and realized it made absolutely no sense. Sometimes, it was awkward, sometimes it was just plain silly.

But on the whole, it was the most perfect thing she had ever read in her entire life.

(A Bottle of Wings and Other Things)

What continually engrossed me was the way the characters were projected or reflected off the insects. There is only one implied Kafka-esque transformation at a point, and nothing too obviously allegorical – like say, an Animal Farm-ish interpretation of real life events. The insects are just there, either like a spectral presence in the background of real life or as an accompaniment of eerie proportions. Like in this story of a father who has an infant daughter that persistently throws herself off of edges and ledges into thin air:

A few nights later Ilango dreamed he was lying on the roof of his house, watching the afternoon sky. Even though the sun was out he could see clutches of green and orange stars blinking above him. He stretched out his hand and something circled down and landed on his palm. It was Muhil. Two tiny wings had sprouted from the knobs on her shoulders. They looked like dried leaves.

“So it’s you!” said Ilango. “Those are very pretty wings you have.”

Muhil looked up at him and bared her teeth; they were round and white.

“Why won’t you talk to me,” he asked. “Why won’t you say anything?”

She stood up and began to walk across his palm, her wings rustling behind her like paper.

“Everyone thinks I’m a terrible father, because you keep trying to break your head open. I wish you would stop doing that.”

Muhil teetered forward, the edges of her wings stabbing awkwardly at the sky. They reminded him of a dead tree.

“You will be the world’s first flying doctor,” mused Ilango. “Or flying lawyer. Or maybe you could do both. What do you think?”

Ilango watched as she tipped over the edge of his hand and spun out into the sky like a dying moth.

“That’s all right,” he said. “You can tell me later.”(Flying and Falling)

Insects have been subject and part of artistic depicti0ns for years now, particularly in visual art. The obvious analogy here is to contrast the animal with the human, the natural/instinctive drives with the rational.

My favourite depictions of insecthood in visual art are by Salvador Dalí, who constantly used ants, spiders and other creatures in his paintings. The Salvador Dalí exhibition Liquid Desire, which I practically inhabited for a few months in 2009 in Melbourne, carried several with the ant motifs, most notably:

The Ants

Dalí’s use of ants is most commonly interpreted as a symbol of death and decay, a symbol of anxiety. But, my favourite Dalí painting — quite large in real life, unlike some of his other detailed work — also touches upon an insect-related theme.

Archaeological Reminiscence of Millet’s Angelus

Dalí himself described the female’s posture in the original painting ‘Millet’s Angelus’ as ‘symbolic of the exhibitionistic eroticism of a virgin in waiting, the position before the act of aggression such as that of a praying mantis prior to her cruel coupling with the male that will end with his death’. In captivity, the female praying mantis devours its mate after copulation. Dalí was absorbed by the idea of female predatory instincts present in the natural lives of insects and other creatures, and combined with the scavenging behaviour of ants, used them with particular intensity in his art, especially with hanging folds of skin (like in Daddy Longlegs of the Evening) or dead, vacant orifices, like in one memorable self-portrait involving grilled bacon.

But it is Kevin Brophy’s essay on Kafka’s The Metamorphosis that I find particularly enlightening on insect imagery and writing. Brophy draws parallels between children’s fairy tales and their usage of animals in conveying certain behavioural traits, but in particular talks of the 1986 Paladin dictionary of symbols, where:

…insects are said to represent precision and meticulous thinking: ‘Insects are masters of detail and are often called on, in fairy-tales, to sort out things that have got impossibly mixed and muddled, such as grain and sand. Phobias about insects indicate irrational fear of detailed thinking’… In another dictionary of symbols the insect is an image of a shortened life… The insect can also, apparently, represent semen, particularly the vicious, stinging semen of an unfaithful husband… Insect, apparently can also mean a poem: a poem is a case of metamorphosis, it is a placing together of separate parts and small details to make a strange new articulated whole. The sonnet in English can have the three-sectioned shape of a beetle.

So, to come back to Kuzhali, the presence of insects makes for very interesting reading when keeping some of the subliminal symbolism in mind. In one of the stories, they seem to work almost like placeholders for an object to be filled in by the reader:

The next morning Stalin Rani awoke and the universe stretched over her eyes like a piece of orange bubble gum. She saw a crack in the cosmic egg, elephants mating in a thunderstorm and a broken toilet. She coughed until something hard and black lurched out of her mouth.

“It’s a revelation,” said Shoebox Uncle. “Put it in your mouth.”

“It came out of my mouth.”

“Put it in your shoebox then.”

Stalin began bringing one up every morning. Soon the shoebox was filled with them.

“How come you don’t want them?” she asked.

“I do, I just don’t spit them out.”

“Why do I have to keep them in the shoebox? How come I can’t just throw them out?”

“Because everyone must keep a box of things they don’t understand and can’t throw away.”(The Sugargun Fairy)

At other times, they seem to exist purely as a factual aside in our own humdrum existence.

And then there are the stories that straddle the divide between comic and tragic – do you think you could laugh about a character who keeps cutting herself? Or a girl who leaves suicide notes like love letters to her boyfriend? None of this is strange or even particularly sad in Kuzhali-world. And each is marvellous.

My final point has to do with the kind of literature I’m obsessed with – the real-irreal divide. There are some solid artistic differences between the unreal, the surreal and the irreal. The unreal is usually seen as fantasy/science fiction, where we know that this is not based on our reality as we know it and that requires a willing suspension of disbelief, that the story has its own internal physics and unknown logic that we simply accept and go past. The surreal allows for more interesting things. Dalí and the Paris surrealists described something called the surrealist object – ‘the notion that the external arena of so-called ‘reality’ was to be discredited and dismantled in favour of another internal and mental reality (the ‘real’).’ Therefore, any morphed, imagined object of the mind, sustaining a deep psychic ‘desire’ was considered to be its own version of reality, never mind how irrational or unrealistic it seemed to the external world. Surrealism was a celebration of the internal logic of dreams and imagination.

Irrealism, however, takes it to the next level. The Café Irreal webpage puts across this wonderful elaboration, and I highly recommend reading it in full, even as I quote a relevant portion:

In an irreal story, however, not only is the physics underlying the story impossible, as it is in these other genres, but it is also fundamentally and essentially unpredictable (in that it is not based on any traditional or scientific conception of physics) and unexplained… Put in fictional terms, there is no reason, no motive for the strange events occurring in the story nor is there any protagonist—such as a wizard, scientist, god, or practical joker—making them happen.

… And, in this way, the physics of an irreal story can be said to resemble that of a dream, where events also tend to be unpredictable and unexplained. It is largely for this reason that irreal fiction is often considered to be dream-like in nature, which is a justifiable description so long as we remember that the irreal work is not the relating of a dream that we might have had but, rather, the evoking of aspects of the dream-state within a work of art.

The concrete difference in irrealism is that there is no psychological causation or motivation to explaining the strange or the unusual. Irrealism overlaps often into surrealist themes, but the irreal refuses to analyse or provide easy explanations for the strange.

Kuzhali’s writing, short as it may be, carries a strong vein of the irreal – something that historically, only the very best of writers have been able to do. I am tremendously excited by the possibility that presents.

If you have read her blog by now, you will know she is on an indefinite hiatus because she is working on something – I believe it’s a novel, and I can’t tell you how much I’m looking forward to seeing what comes out of her next.

A reviewer of IaJLYaMESoTHW said that on reading the book she felt like she knew her already, like they hung out at a party or something. I didn’t get that feeling, but now I keenly hope that I do get to hang out with her at a party. Or a park. Or anywhere, really.

Do you know how funny she is in ‘real’ life? Interviews here, here and here.

Also, Tehelka review and Bookslut review (scroll down midway) are decent.

Many of her stories can be found in online magazines and journals, linked through her website, so please start clicking. If you think Indian Writing in English is stale and stereotyped, I don’t know if there is a better answer to that than Kuzhali.

Also, I think I have finally learned to pronounce her name. Only just.

[Note: My references to Dalí’s paintings and surrealist theory are from my exhibition catalogue of Salvador Dalí: Liquid Desire, published by NGV, Melbourne.]

This is probably one of my favorite reviews of my book, am truly thrilled and humbled, thank you so much 🙂

k

OMG Kuzhali! I feel like a giddy groupie!

Can I just say thank you for the most delightful funny read I’ve had in a very, very long time? Also, thank you for commenting. 🙂

This just looks brilliant. As a reader, I am always interested in writing that is strange and wonderful, and there aren’t enough writers writing it!

Yes, there aren’t. I do hope you buy her, George. 🙂

I did! I’m hoping it’s going to arrive very soon, although ridiculous jubilee shenanigans in the uk are no doubt holding up the postal service.